Curating a Homeschool Routine and Curriculum (Overview)

Curating a Homeschool Routine and Curriculum

The conversation started to veer out of control. This other mother didn't know me yet, or apparently many others like me. I wasn't used to the angle of her question.

"I mean, what do you have to do to become a homeschooler? They should have protections in place."

"You usually just write a letter-- a statement of intent--- and register it with the school district."

"But, I wouldn't know everything I was supposed to teach my kids. What do you have to do to qualify as a homeschool teacher?"

"Uh ..." Be a parent?

"Because, what if just anyone could homeschool their kids? Lunatics and uneducated hermits and ... I mean, who's watching out for those kids?"

"Yes, I suppose that is a risk, but ..." We don't all live in the woods, lady.

"I'm sure the government has requirements in place: like whether you have a teaching degree, and what exactly you have to teach ... they probably have people checking in on you and a mandatory curriculum, because parents don't know everything a child ought to learn."

"Do you think the government is better at knowing what a child needs to learn than parents?"

"Yeah! They have experts, they've done studies."

"But children are so different from one another. They learn in different ways. Their parents know them better than anyone. Not to mention that they love them with nearly endless patience. So parents can design their own curricula to match each individual's strengths and weaknesses. The curriculum can take into account what they're passionate about and what they need most, and--"

"WHAT! You mean you can just TEACH them WHATEVER you WANT?"

I blinked. The silence told me that by now, everyone was listening. I blinked again. "Yeah."

I will post later on how we approach individual subjects. This overview shows how we select our subjects and budget our time. I revisit this process at the beginning of each school year. How do you pull it all together? This is how I wrap my mind around the whole project of homeschooling. Once you've realized why you want your kids taught at home, this is the next decision, the how. When someone asks me "what curriculum do you use?", it is the long answer. Sometimes pieces of it may indeed come out of a box, but it doesn't have to. It comes out of a bag, I suppose, flexible and expansive, the woven fabric by which we define ourselves as learners.

Step One: Watch your child play.

Hold on a second-- maybe I need a step zero. This would be a good time to file your paperwork with the school district, before you forget. Check the laws; jump through the hoops. Get it over with, because this is the easy part, but it's not the fun part. There. Put a stamp on it, and now you're legal. Move on to the fun part.

Step One: Watch your child play.

Ask yourself some questions.

Are they happy?

What makes them the happiest?

What are they afraid of?

What are they creating?

What are they really good at?

Do they struggle in a particular area? Could you approach it differently somehow?

What do you love to learn, and how can you share that (not in order to replicate yourself, but to let your passion be contagious)?

Far into the future, if someone were to ask them what they learned from their parents, what they cherish--what would you want them to say?

What are the most important things to learn?

Is there some way you can give them a magical childhood and an education at the same time?

Reflecting on who they really are gives you the cornerstone for a curriculum. Don't be afraid to have different answers for different children. Don't be afraid to linger on this step for as long as necessary (especially if you're transitioning from public school-- we call that a deprogramming period). When something isn't working, this is the drawing board I return to. Here are some of the observations about my own children that have evolved into a specialized curriculum:

- [C.] learns by teaching. She loves to lead, partly because her peers are a laboratory for testing what she's learning. Social learning experiences will engage her.

- [A.] has a knack for music theory.

- I want them to know that I love them.

- [C.] thinks she hates math worksheets, but when I add a timer, she eats it up. Play math games.

- [A.]'s mind can handle more advanced math than his motor skills, so worksheets hold him back. Allow him to answer problems orally in the meantime, but incorporate fine-motor-skill play to help him develop.

- I want them to love learning, not dread it.

- [G.] loved storytime before he was born.

- Reading wonderful books is one of the best ways to study anything. I love to read to them, and can easily be passionate about words.

- When they're in the woods, they sing. Spend time in the woods.

- [C.] is motivated by praise. Can I teach her to find praise from within?

- [A.] is motivated by imagination. Remember to have a sense of humor and to turn work into play. Better yet, teach him how to turn work into play himself.

- I want them to have academic courage; to know that they can put their mind to anything. Avoid outsourcing every subject, but instead instill research skills, a sprightly sense of pursuit, and an opportunistic resolve to call upon and work beside experts. Be a "hackschooler". (Thank you Logan LaPlante)

- [C.] is really good at memorizing. Use this for good, not for evil.

- [A.] is really good at battle strategies. And we have an ever-growing armory in the dress-up box. There's my approach to history.

The point here is to start the process by following the child.

Step Two: Draw a map and prioritize

Mind-mapping

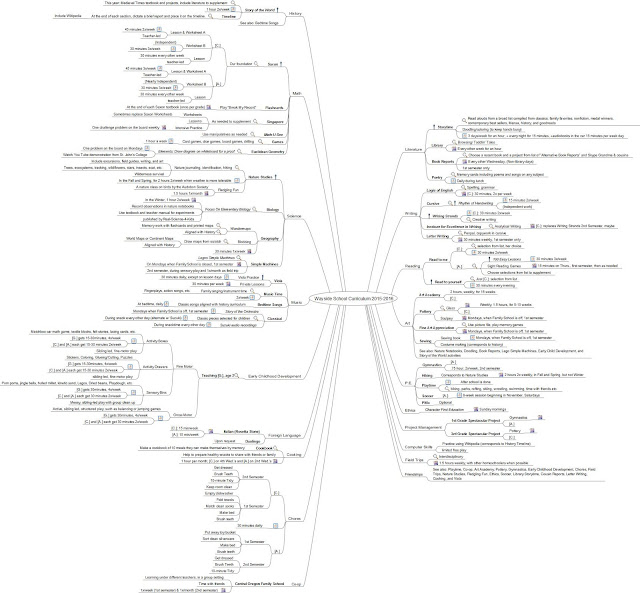

Grab a piece of paper, or this awesome, free mind-mapping tool, and map out which subjects you would like to study. Arrange similar subjects together, so you can see how they reinforce one another. "Reading," for example, can be a main branch, while "going to the library together" can twig from there.

Highlight the ones that are truly important to you, which you meditated over earlier. This year, I highlighted storytime, reading lessons for [A.], cursive, creative writing for [C.], independent reading for [C.], history, viola lessons, Saxon math lessons, and nature studies. They are what I felt we really needed to concentrate on. On your map, note how you'll approach each subject, the titles of resources you plan on using, and which students will participate. Later, you can add-in how often the subject is studied (i.e. daily, for 30 minutes.) At first glance, my map looks absurdly complicated, but this exercise is weirdly reassuring. I only gained one or two new subjects each year, but have included educational elements that were already integrated into our lifestyle, such as bedtime stories and cooking. It's that moment you gather all your pocket change together and realize you have several dollars worth in coins. They're already learning so much! We just want to be sure we're making time for what's most important. Utilize branches to help you visualize gaps. Here's a simpler map, as if my oldest was a young preschooler:

Or, maybe try using a hackschooling model:

My main branches, or subjects, are Literature, Writing, Reading, Art, P.E., Ethics, Project Management, Computer Skills, Field Trips, Friendships, History, Math, Science, Music, Early Childhood Development, Foreign Language, Cooking, Co-op, and Chores.

I was about to show you a Common Core example, but I'm not sure why anyone would want to put themselves through that, so, sorry. I wouldn't over-complicate this by turning it into a master syllabus, "aligning it," or scheduling chapters in textbooks. I am not talking about the kind of mapping school teachers are required to do:

Yikes! That is not necessary in a homeschool setting, because you're not turning this in. You don't have to compare students. You have the freedom to take your time if your child is "behind" in something. You're just getting subjects down on paper and determining resources so you can see what it adds up to.

Choosing Resources

So, you've prioritized your subjects-- how do you select your resources? Sometimes non-homeschooling moms look at me with wide eyes because they think I am designing my own curriculum from scratch, staying up late every night scripting my lessons for the next day. I'm not. (All my prep. work between school days can be accomplished in the five minutes it takes me to reload their responsibility charts) That would be a lot of work. And there are loads of people who have already done it for me. I take advantage of their labor and find it at a discount. I'm curating rather than creating. Now before you start Googling things like "homeschool spelling curriculum," pause to ask yourself how a given subject is best taught. For example, what history lessons do you remember most? The one where your class dressed up in togas and reenacted the assassination of Julius Caesar? Because you pretended for a moment that you were someone else, and it made that person come alive, right? There are clues in the lessons that stuck with you. They tell you what kinds of resources work best. I can trace all of my pre-high school study of grammar back to one short booklet, read in one week in the 7th-grade. It was a breeze! I hadn't needed to spend years memorizing the definition of a gerund. I learned grammar best by reading a lot of fiction, not by keeping pace with a language arts curriculum. I take this to heart when shopping for resources.

|

| A memorable introduction to the Union and Confederate armies at Shiloh |

There are other ways to make your selections count. Search for reviews. Homeschoolers love to write reviews. Shop for used items (except for "consumables," like workbooks, which are usually better purchased new). Read homeschooling methodology books, or websites (an example, another example) to narrow down your choices (but not to limit how you define yourself.) Join a local online community, and meet others that inspire you. Find out what they use. I happen to really enjoy this conversation, and I don't think it will ever get old. We're an opinionated crowd that can't wait to share. Try going to a convention or curriculum fair.

I have a personal rule that has saved me a fortune. I'm not allowed to buy the next book until I'm nearly done with the one I'm using. (Assuming, of course, that it is working well.) It is extremely probable that I will change my mind or find something exciting and never use the more advanced book I bought. There is so much out there. Resources go way beyond books. The local Audobon Society teaches free classes. There's that nature trail five minutes away. The library offers free lectures. The next door neighbor can immerse them in a foreign language while you rake her leaves. My backyard is littered with math-manipulatives and science projects that can be reused as art media.

|

| Graphing--with resources we had on hand |

Schedule vs. Routine

I have tried to be a schedule-person, but with practice I find that I am not. I am a routine-person. It means that I like to get everything done in order, but I prefer not to have the stress of getting them done on-time. I'm swapping punctuality for flexibility. This is reflected both in our daily reality and our annual reality. If we don't finish our art project by 3 pm or our history book by June 15th, it's no big deal. We can roll it over and go at our own pace. That said, I do like to generally stay on grade-level with math. I try to make sure I'm about halfway through the book when I'm halfway through the year, and adjust as necessary. How do I keep track of which lesson I'm on if I don't make a syllabus? I use a bookmark.

If you are a schedule-person, this might feel a little tenuous to you. That's fine! Celebrate! You're a schedule-person! Take some extra prep. time before the school year begins and schedule your lessons. There are some beautiful benefits to being a schedule-person, like knowing you'll be reading Call of the Wild in the 1st half of February so you can schedule a dog-sledding field trip to go with it. Many of my favorite homeschooling mentors are self-proclaimed schedule-people, and it works fabulously. (If you don't have a mentor like this, you can borrow one of mine.)

I'm not at the other end of the spectrum either. My map may look overwhelming, too organized ...even when you adjust for a margin of flexibility. Maybe you are an anti-schedule person. You are drawn to natural learning. You are opportunistic. You are good at following your child and embracing educational moments when they come your way. There are beautiful benefits to homeschooling without a routine. Like feeling the freedom to spend the rest of the day building a catapult, or designing a labyrinth, or learning Morse code, because you read about it and it caught your whim.

By the way, you can be a schedule person and an anti-schedule person, all on the same day. Chances are, one of your kids will be your opposite, so you might as well know how to do both.

|

| The chore chart that didn't work, because we have two anti-schedule people in the family. |

Step Three: Schedule (just to see if it fits)

Don't worry, we don't keep to this rigidly. Even though I am not a schedule-person, once I have my map telling me what I want to accomplish, I plug everything into a schedule to see what I am actually capable of accomplishing. It never all fits. Not even close. But I would rather realize this on my own than figure it out with the kids as casualties.

I use Google Calendar for this, because it syncs to my phone, community events, and because I can look at more than one calendar simultaneously. My students each appear in different colors. It allows me to seize more opportunities to teach multiple children at the same time.

This works the same whether I have only one child:Don't worry, we don't keep to this rigidly. Even though I am not a schedule-person, once I have my map telling me what I want to accomplish, I plug everything into a schedule to see what I am actually capable of accomplishing. It never all fits. Not even close. But I would rather realize this on my own than figure it out with the kids as casualties.

I use Google Calendar for this, because it syncs to my phone, community events, and because I can look at more than one calendar simultaneously. My students each appear in different colors. It allows me to seize more opportunities to teach multiple children at the same time.

Or seven children:

With this tool, you can multitask like a robot. I'm not adding every single event, just repeating it (chores, for example, repeat daily, and music lessons repeat weekly.) I can then copy that event to another student's calendar. "Sorry, buddy, you get to do chores too." I love using Google Calendar because I can customize how I want my events to repeat. For example, I want to attend Library Storytime every other week until June, and I want a pop-up reminder that morning, and on the alternating off-weeks, I want to do book reports instead, and I want to invite Grandma. The events are searchable (say, how many more math lessons do we have left before summer?). You can add details (like chapter numbers, if you're a schedule-person, or google maps and contact info, if you know you'll get in the car for that field trip without having time to find out where it's located.) Past events remain in the calendar. (Aha! Now you have automatic attendance records. I stick to the plan, more or less, and if something unexpected cancels school for the day, I delete it. It's easy to determine whether we're meeting our state's quota of instructional days.)

With a few exceptions, I find it convenient to make each week match. So each Monday has the same routine, and each Tuesday, and so on. If you want an even easier agenda, make each day match. This would be a good choice with very small children. We were willing to make ours more complicated for variety. If the last day of the month falls on a school day, we call it a Jubilee Day, and the kids get to pick their own educational subjects.

|

| Jubilee Day |

It's a bit overwhelming to get my map to fit on a calendar, so I use this process:

- Add appointment events first, like pottery classes, Karate, physical therapy, etc.

- Jot down a mental list of which subjects can be studied all together (like history) and which can be done independently (like a math worksheet, or studying a foreign language on a computer)

- Fill in what the siblings are doing during the appointment events. Until this year, my youngest just joined in. (By the way, "Baby Years" are special homeschooling years. Mom gets to break as many rules as she wants, because everyone is learning so much about parenting. You also get to take A LOT of short and unpredictable recesses.) Now my youngest is two, and too young for preschool, but too old to stay out of the way. I use the buddy system to engage him with sensory play when I want individual time with another student. This is the great secret to multiple-level homeschooling. (Geez, I think it's hard and I only have three kids.) We have learned to survive! I will go into more detail in the post "Early Childhood Development."

- Place your priority subjects in the the choicest spots. For many, that's the first slot of the day. If you are lucky enough to have a naptime, (not you, ha ha, the baby) use it ferociously. Last year, I did our daily tasks in the same order each day. That is, reading lesson always came after breakfast, viola practice was always last, etc. At the semester break I flipped the agenda upside down and noticed that their favorite subjects became their least favorite, and vice versa. Interesting. This year, although it's more complicated, I mixed it up a little to avoid the ruts. It evens things out.

- You don't have to study everything daily. I like spending at least two hours on Nature Studies, for example, so we just do it two or three times a week.

- Lastly, fill in the cracks with everything that's left. If it doesn't fit in the suitcase, leave it behind.

- Decide what time school "ends." I used to just let it drag on and on until the kids were done. Dinner felt neglected. Now we have a goal, coinciding with when their friends come home, and I incentivize the timely completion of school with allowing privileges such as computer games. I also motivate them with the misnomer "homework," which in our case means, "if you don't do this now, (or at least by 3:00,) while I am here supportively helping you, you'll have to figure out how to do it all by yourself. In the meantime, the rest of us will move on with our lives." So far that has worked every time. Sometimes I can tell a child needs more compassion that that, because they are truly struggling. We take a break with that task, surge ahead with our routine, and come back to it later in the day with renewed courage.

- Keep an "empty shelf." After all, when are you going to make dinner... answer your messages... go to the bathroom? You'll be glad you did.

|

| An example of the "buddy system" |

I just discovered clipboards last month. We get any worksheets out of the way on clipboards during siblings' lessons. It frees us up at home to do more projects. While [C.] is at her art class, I take [A.] and [G.] to a park. [G.] plays and [A.] flies through his cursive practice and a math worksheet so he can play too. He is more efficient, and we also get sunshine and exercise. Last week, he found a stick and practiced his cursive in the snow. Then we walked for miles along the river and through the dog park while I made up math questions about what we saw.

|

| An example of clipboard schooling with one child, while at the park with a 2nd child, during a 3rd child's art class |

Now for some rules about events:

- For each time block, include both the transitional time it takes to get into a subject, and the clean-up time it takes after. Or you will go crazy. For example, from the time I call my son for his reading lesson, to the time I call my daughter for her next task, 30 minutes will likely transpire. The first 8 minutes were spent getting him to sit down, because he has a

leakycreative attention and needs a lot of redirecting. I spend 2 minutes pulling out a sensory bin for [C.] to use in occupying the toddler. 5 Minutes are spent "warming up"; I am finally able to get [A.] to look at the first word and sound it out. I am then interrupted for the next 8 minutes because [G.] is potty training and needs yet another bath. I spontaneously think of a crazy game we've never tried before and [A.] becomes super-focused, for 5 minutes, when he zips through 120 more words in one breath, completing the lesson. We have 2 minutes to go, which are spent putting away the reading book and helping [C.] and [G.] clean up the sensory bin.

The fact that only 10 minutes out of 30 were spent learning the subject is not one to bemoan. He was focused on something difficult for 10 minutes! He's five, and that's wonderful. He deserves to play outside after that. It's enough. How much individual attention do you think a public 1st-grade teacher gives each of their 23.1 students in a school day of 6.64 hours? Each student would get 17 minutes of his teacher's attention, if there were no breaks, no group lessons, and no interruptions. So couple these 10 productive minutes of reading with 10 minutes of some other subject, and you're already at an advantage when it comes to one-on-one time. Even when I'm not comparing our productivity to the public standard, I still feel like my son's 10 minutes is commensurate to his age. He reinforces the new material he has learned through active play. I happen to have strong opinions about the educational merits of unstructured playtime, if you haven't guessed by now.

That's my only rule. Give yourself plenty of time for each event. Don't forget travel time, snack time, and an extra long lunch so you can sneak in some dishes and laundry. I have learned that if I don't at least start a load of laundry in the morning, change it once at lunchtime, put away the food, rinse the dishes, and wipe the table, we can't tread water with the housework and we end up going under. We can't function on less. Obviously, it would be nice if we got beyond these basics, but school comes first. Your minimum may be different than mine. Whatever it is, make space for it in that schedule. You want to be realistic and have a fighting chance at sanity.

Turn the "schedule" into a chart your kids can understand. Last year, our chart was simpler which allowed us to memorize it after about two weeks. We never even had to look at it. It is helpful to get started though.

I bought hundreds of business card-sized laminating pouches a few years ago (on Amazon) and velcro dots (on Amazon). This way I can physically remove the card from the chart during school, so they can easily see what they have left to accomplish. My kids like the tactile reinforcement they receive when they take a completed task off the chart, ripping the velcro apart. I also laminate the charts, hole-punch them, and put them on book rings like a calendar. Someday, if my kids are ever mature enough to have devices, we can skip the chart because they will be able to access the calendar themselves. When I notice that a child has taken the initiative and completed a task independently, I make a big deal over it. "Whoa! You did that all by yourself? Let's put a sticker on it so that next time you see it, you remember that it's something you don't need me for." Bingo. Next week maybe they surprise me at breakfast with the announcement that they're already half done.

Step Five: Organizing Your Space

Eh, I'm not going to dwell on this, because you are probably doing just fine already. The most important feature in a homeschool room is the floor. Seriously, we use it all the time. For everything. If you've got a floor, you're set to go.

But, homeschooling is messy, right? The advice I repeat to myself is to keep things where you use them. Our pencils are kept on the desk. Our library books are next to the bean bag chair. Our shelves are full of countable objects that I can grab easily to demonstrate mathematical concepts. Our outing bag remains packed, ready for the wild. Our musical instruments are hanging on the wall, just begging to be played. That awful reading curriculum that was pushed on me with the yucky comprehension questions? It's deep in storage. And now, groomed photos showing what my schoolroom looked like that one time it was clean:

|

It's not a bad thing that the schoolroom doesn't stay tidy for long. When it is tidied, it's awfully inviting. By the time I've put the vacuum away someone has started a new project. I'm learning to take it as a compliment.

We don't have a playroom, because the toys stay out of the schoolroom. (Consequently, we don't have a functioning family room, because it's full of toys, but ah, well--those are the choices we've made.) Despite the ban on toys, this room is full of play. It is where my school toys go :). The toddler keeps busy designing his own art forms, playing with math-manipulatives, and dumping board games out on the floor.

In an effort to be more Montessori, we have activity boxes and sensory bins pre-filled with educational objects he can use on his own or with a buddy.

|

|

Sensory Bins are kept in the closet, released with permission only.

In an effort to be more Waldorf, we keep natural objects handy. I never would have imagined the variety of applications for the things we have kept in jars and bowls. We use them, for history, science, writing, math, fine motor practice, art ... because they are there, not because I had planned to use them. There are beads, marbles, paperclips, pennies, seashells, brads, tiny rubber crocodiles, toy bugs, buttons, clothespins, googly eyes, unifix cubes, book report ideas, base-ten blocks, dried beans, wooden cubes, felt numerals, playing cards, river rocks, homemade phonogram bean bags, feathers, bouncy balls, sticks, and pine-cones. In case you're wondering, it was messy for the first few weeks. We did eventually learn the wisdom of cleaning up as we move along. Even the two year old.

|

| See all that dust? Proof that this is an honest picture. |

|

Yes, I really do need 11 separate containers of Elmer's glue. My favorite pockets? Definitely scissors. And

|

|

So, that's the schoolroom. However, don't think we spend 7 hours a day in there. The rest of our home is an extension of it, because we're parents teaching the whole child. So we study in the music room, and conduct experiments in the kitchen.

We read on the front porch, and on the beanbag next to the fire.

We watch YouTube videos on the computer, and finger-paint in the laundry room.

When we tire of our little schoolhouse, we leave. We study in the community. We're at the library, the museum, the art studio, the ocean ...

Hooray, for my first mudroom. One of my biggest fears about homeschooling is that my kids seem to have a really hard time wearing shoes. And getting in the car on time. Hence, the mud-closet; with shoes, socks, snow clothes, backpacks, and "outing snacks" (if we keep portable food in the kitchen, we eat them too freely). This year, I decided to pack an outing bag that is more comprehensive than my smaller diaper bag. If we've just got one quick stop, I bring the diaper bag. If we're going to be gone long enough to need a snack, or if we're going to be spending time in nature, I bring the outing bag. Along with water, my ERGO carrier, bear spray, and a first aid kit, it is also pre-packed with watercolors, colored pencils, nature notebooks, spare clothing, and field guides. The easier it is to get out, the more likely it is that we'll go. I have the example of my awesome mother to thank for this one. (Well, to be honest, all my good ideas were hers first.)

|

| Our other schoolroom |

Step 6: Don't Take Your Routine Too Seriously

Just have fun. Take departures from the schedule to fit the family's needs or just to combat monotony. Sometimes I notice we're dredging along and I make spontaneous changes: "let's do things backwards today," or, "let's skip ____", or "it's nice outside--let's do school al fresco, in the fresh air!"

|

| An al fresco Day |

Appendix

Summing It Up

After I schedule my routine, I go back to my mind map and add duration and frequency to each subject. This isn't necessary. I was just curious. If I add up each subject for a week, estimating how she spends her leisure time, and create a hypothetical "average school day," this is how my 3rd-grader spends her waking hours Monday through Friday:

If we finish a task early, I call recess. I love saying that ... "okay, we're done 15 minutes early ... go play." Sometimes we're in the mood to race ahead so our school day ends early. Time to play is really important. This is one typical day for my 3rd grader:

She has a 30 minutes of recess at 8:00, 30 minutes of recess during snacktime, and 75 minutes of recess during lunchtime. That's 1.75 hours of recess on Thursdays, all before we "let out" at 3:00. But, that's only if she dawdles, because I've built dawdling into the schedule. If she's efficient, she gains an extra 1.25 hours of earned unstructured playtime. This is what her day would look like then:

7:15-7:30 Chores

7:30-7:45 Viola Practice

7:45-8:30 Recess

8:30-8:45 English

8:45-9:00 Recess

9:00-9:15 Early Childhood Development

9:15-10:00 Recess (& snack)

10:00-10:30 Math

10:45-11:00 Early Childhood Development

11:00-1:00 Recess (& lunch)

1:00-3:00 Art Academy (with friends)

She gets in a few other subjects (cursive, math, chores, reading, and storytime) at night or while [A.] is at gymnastics, equivalent to the public schooler's "homework." In total: 3 hours of recess during school, a free afternoon, and including our evening routine, 5.5 hours of efficient, productive work.

Contrast this to my nephew's [public] school day:

No recess, other than the 23 minutes reserved for lunch.

Fortunately, my nephew has awesome parents who put pressure on his school, resulting in a healthier schedule.

As homeschoolers, we get to make another division beyond distinguishing recess from book-work. I'm going to call it "Experiential Learning." If we read up on photosynthesis and then conduct an experiment, the experiment part is experiential learning. Cooking ribs for dinner to "practice being a grown-up" is experiential. Holding worms, painting the kitchen cabinets, mastering a back-handspring, teaching a younger sibling how to count, or following-up on a resume is learning by doing. It is active, it is tactile, it is real.

Book-work is not bad, as it can also be creative. It isn't necessarily passive, either. Drawing a map or writing a story or using a computer is book-work because they're sitting when they do it.

My purpose for the division between book-work and experiential learning is both to ensure that my children are spending enough of their childhood moving and also to help them better retain the knowledge they are gaining.

[C.]'s "Average Day" would be divided like this:

|

| Early book-work |

My purpose for the division between book-work and experiential learning is both to ensure that my children are spending enough of their childhood moving and also to help them better retain the knowledge they are gaining.

[C.]'s "Average Day" would be divided like this:

That's how I like it: plenty of play, an abundance of experiential learning, a little bit of book-work.

|

| "Book-Work" |

|

| "Experiential Learning" |

“For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyreplayers by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.”

― Aristotle

Smelling Like Dirt

Our theme for this year, hanging in the schoolroom, is a quotation by Margaret Atwood: "in the spring, at the end of the day, you should smell like dirt."

At the dinner table on our first day we discussed how we are in the spring of our lives and what we want to accomplish with our time. We are getting our hands dirty. I hope that this education stays with them--that it gets under their fingernails.

I hope that they remember the way it felt, and the way it smelled.

I hope that at the end of it, they can stand up, stretch, and taste what they've cultivated.

|

| Grown in our backyard |

Wow! So much, so much and so fun. Your children are blessed by your devotion and creativity. Yes, and I especially enjoyed the part about your wonderful mother. I love you so much!

ReplyDeleteYou must be cringing :)

Delete